Product Design Mechanics #2: How direct network effects are at the core of many social phenomena, why they count among the strongest Product Design Mechanics, and how to bake them into your own products.

South Tyrol is a place designed by Gods for their own delight. Sublime mountain ranges, rising up like sharp daggers into the sky. Vineyards and soft green hills wherever the eye may reach. Miraculous cities enshrined by the beauty of nature.

One of those miraculous cities in South Tyrol is Merano. There is a golden light in fall that rests upon the very city. Mediterranean palm trees meet majestic mountains. There is a certain medieval touch to it, turning Merano into an enchanted gem.

Ethereal memories

My family and me were meandering the streets when my two little daughters, 2 and 4 years old, were magnetically drawn to two street artists, dressed in medieval guise, casting giant soap bubbles that a crowd of merry kids was running after.

My wife and me looked at the scenery and rejoiced in all its splendor, our gaze resting on our girls as they were also running after bubbles, making them burst, laughing. My little daughter had managed to burst the entire flock of bubbles she pursued, except for one. It was not a big one, rather mid-sized. Florentine stood on her toes, she jumped, but the bubble was gone, beyond the reach of her little arms. Rising up into the air, into the clear blue sky over Merano, in one graceful and smooth motion. And then the bubble was gone.

That moment would stick to me, would not let me go. It had something eternal and celestial about it. And I wondered how I would contemplate that treasured moment in many years from now, when Florentine and Eleanor were not those little girls anymore, merrily hunting for bubbles …

However, there was one thing about the entire scenery that did not fit the overall guise. Something that created a cognitive dissonance in me:

To mask or not to mask

It was October 19, 2020, and the world was fully consumed by the second wave of the Corona virus, also called Covid-19. Almost everyone on the streets was wearing a mask to protect herself and all others around her. Even though this was not mandatory, not outside, not on the very streets. It was just a governmental recommendation to do so.

This was a huge difference to Germany, where masks were likewise recommended outside (and required when in shops or public buildings) – but worn by few people only.

I was wondering how that could be, why the people in Merano would wear those masks voluntarily … while the people in, e.g., Munich, would not. Even though the regulatory requirements were pretty much the same.

And here we are, looking right into the face of one of the strongest Product Design Mechanics (PDM) you can think of:

(Direct) network effects.

Let’s assess the whole thing a little more deeply: The probability of people wearing a mask is determined by their immediate social surrounding. If none of the people around you wear masks, chances are high you will not do it either. As it is the case in Munich.

On the other hand, if many people around you wear a mask (mind that a mask is a tool rather to protect others than yourself), chances are high you will wear one, too. This is a simple matter of people staring on you and of social pressure.

That said, the probability of you wearing a mask is proportional to the share of masked people around you. Certainly, there is a glass ceiling to it as there are always people that do not bow to social pressure and refuse to wear a mask, no matter the share of wearers.

That’s why a majority, but not everyone in Merano wore a mask.

The fact that the odds of you wearing a mask is (roughly) proportional to the ratio of wearers around you triggers a self-reinforcing cycle: When you feel urged to wear a mask and put it onto your face, the ratio of masked people in the immediate social surrounding increases … which in turn increases the probability that other people will put on their mask, too. And on and on.

This effect of self-reinforcement is also called a “rich get richer” phenomenon. In our case, “rich” would refer to the mask ratio. When a certain tipping point of mask wearers is exceeded in some geography, the whole system takes off all by itself. And will lead to a situation as the one described in Merano.

The omnipresence of network effects

When the mechanics behind direct network effects (and what they mean to product design) are not clear to you yet, do not worry. For now, it was my goal to show how those direct network effects appear everywhere, even in places where you would not expect them, like the enchanted alpine city of Merano.

As said before, direct social network effects are amongst the most powerful PDMs. Once they have been successfully established in your product, they are hard to beat. Because they are hard to build up in the first place. But soon as they have surpassed the before-mentioned tipping point, they become self-sustaining, even self-reinforcing. Rich get richer, here we are.

It’s not about the product

The most obvious occurrences of direct network effects are in social networks: Facebook, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, XING, and the like.

All these social networks have in common that their true value is not the digital product, its UI, UX, the portal or mobile app. It’s the sheer number of relevant users they are able to summon on a monthly, weekly, and daily basis. This is the true pot of gold and the reason why they are so hard to beat.

Not convinced yet?

Think of a copy of Facebook. Let’s call it Hyperbook. It’s a better version of Facebook, for sure. You like the UI more, you love striking features like total immersion thanks to VR, you like the ability to use it just by means of speech control – which works perfectly and features the best speech-to-text translation you have ever witnessed …

Are you sure you will use it more than Facebook, given its product superiority? I bet against it. Because for one simple reason: Hyperbook is new and none of your friends are there.

Other than, say, a newspaper, a social network’s user value, also called utility, does not come from the product itself. But from the people using it. You use Facebook for the sake of keeping up with what your friends do. If your friends are not here, then, well, you won’t be there either. The more of your friends are on Facebook, the higher the likelihood of you joining and using that network, too.

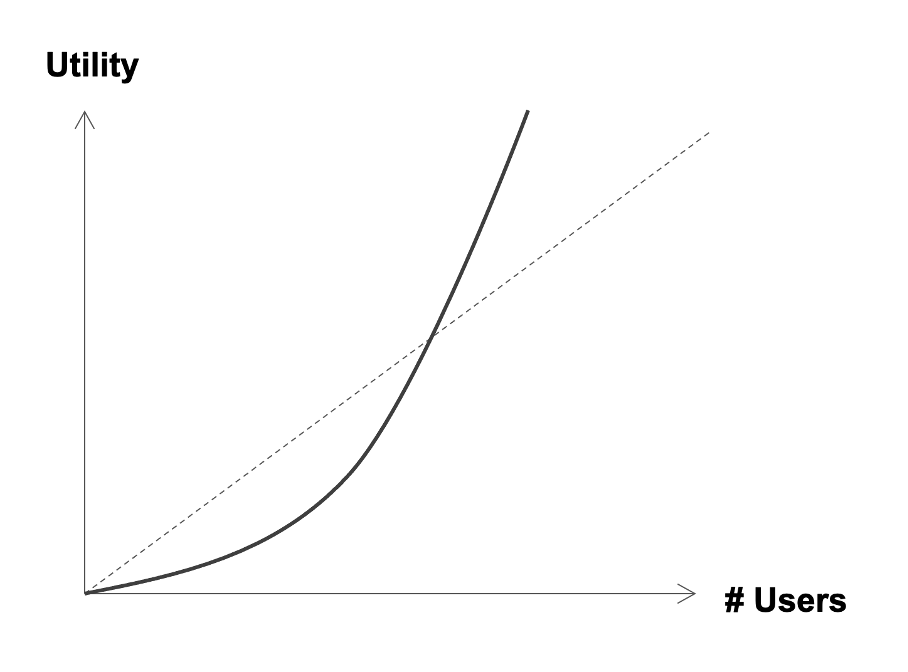

Newcomers in social networks, like the above quoted demon of our own design, Hyperbook, are fighting a bloody uphill battle if they want to challenge incumbents. This is shown in the below figure, where you can see that direct network effects are hard to build up, but will shoot straight into the sky soon as they have surpassed the tipping point … created by a “pull” effect where you as user just cannot afford not to be there – will you, nill you.

In contrast, when you read a newspaper, the value of that newspaper for you does not increase when your friends read it, too. The content is the same. No matter how many of your friends read it, too. There might be a little benefit in being able to discuss the articles that all of you have read. But that’s it. The content is nevertheless not any more valuable to you. So, newspaper articles are not driven by direct network effects. And thus are, as a business model or product, not blessed by sky-high entry barriers. When a better newspaper comes along, with articles you like more, written in more complacent language, you will likely switch to it. No matter what the people around you do.

Direct network effects do not only appear in social networks. They extend way beyond. Like the Merano story, an excerpt of my very life, has shown. Like the example of the hegemonial battle of Microsoft versus Apple during the eighties – featured in the introductory chapter on PDMs – has shown.

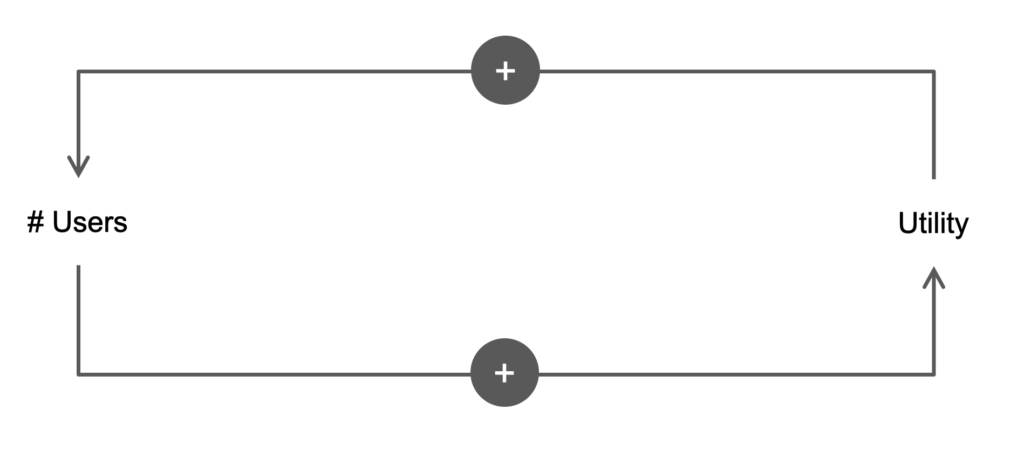

The mechanics are always the same: the value of the product, its utility, is not driven by features, design, etc. It’s driven by the number of users using it. The more, the better. When surpassing a certain threshold (the tipping point), a virtuous circle is triggered, as shown in the below figure.

It is noteworthy that network effects can well be limited locally – both in a geographical as well as social tie-related sense: There could well be a super-local Facebook, let’s call it Localbook. Suppose that everyone in a given village is on Localbook, but no one outside the village. As long as Localbook users are only interested in keeping contact with their village peers, the utility of Localbook is still as high as it can be to those village dwellers. The entry barrier is already sky-high.

The same holds true for locality based on social ties: If you are in search of a platform to keep up with your mates from college, then a social network that features all (or most of) the alumni of that college and no one from another still maximizes its utility for you as an alumna.

This is actually how Facebook (and I now mean the real Facebook, not some hypothetical copy or variant) conquered the world. Remember that social networks are hard to build up. If there is no one on that network, why should you bother and join? Facebook overcame this difficulty in its tender beginnings by conquering one college after another. A college (i.e., the sum of all its students) is much easier to conquer and push beyond the tipping point than an entire state or country. Soon as there were enough conquered colleges across the nation on Facebook, the social network could also spread beyond academia.

Locals only

Let us revisit local network effects based on geographic proximity, the Localbook example. There actually are networks like these, e.g., nextdoor.com in the US, or its German copycat nebenan.de. They intend to take neighborhood to the digital space, where neighbors of one hood can sign up and connect, stay in touch, trade things, etc.

Both, nebenan.de and nextdoor.com, are social networks. When in fact they are not one social network each, but a cornucopia of social networks. In fact, each neighborhood can be seen as a social network of its own right, driven by its own direct network effects. When you sign up for one of the two digital platforms, say you go for nextdoor.com, you only care whether your direct neighbors are on it. If all your neighbors are on, but if nextdoor.com was unknown to anyone beyond, you would not bother but still see your utility maximized.

Overall network size, the overall number of all users on nextdoor.com, would not count. Only the number of users of your relevant neighborhood. In my eyes, this is the reason why nextdoor.com had a hard time (and eventually failed) attacking nebenan.de in Germany: nebenan.de had already established many local neighborhoods (with strong penetration and strong coherence) in Germany before nextdoor.com decided to spill over to Germany.

And when you as a user are part of an active neighborhood on nebenan.de, with a major share of your neighbors being on that very network, why would you contemplate switching to the overall bigger network nextdoor.com? It is of no use for you that there are thousands of well-established neighborhoods in the US. That’s why – in my eyes – nextdoor.com failed to push nebenan.de aside when entering the German market.

Baking network effects into products

Next to social networks, there are a plethora of examples of network effects at work elsewhere. Many of them have to do with data and the value you get out of it. Look again at the self-reinforcing circle sketched before:

The more users, the more value, the more users, …

Google Maps is not a social network. And yet it is, in an implicit way. One of its main drivers of its huge success is network effects: I use Google Maps not only because the map material is good and route finding works pretty well. But because it boasts the best, most accurate and up-to-date traffic information.

This is where network effects come into play: The traffic information is not generated by dedicated surveillance personnel roaming the streets as part of their job, like in the good old days of traffic radio. If you use Google Maps, then you are that surveillance personnel. Because traffic information of each user is transmitted to Google, allowing Google to analyze and deduce where traffic flows smoothly, but also where traffic jams happen (because the signals of those users flow very slowly).

The more users, the more accurate traffic information (plus projections of riding time) becomes. The more accurate the information, the more users are torn to Google Maps. And on and on …

Creating platform economics

Platform economics, a term that is often heard of in our days, are based on the PDM of (direct) network effects, too. With XING Events, the company I had the pleasure of being CEO of before joining immowelt, we started a similar play:

XING Events is a company that offers services to millions of organizers, so they can manage and orchestrate their real life or online event. Services like event promotion, ticketing, entry management. Services that per se do not boast network effects – no organizer benefits from XING Events offering that same service to another organizer (except for economies of scale, of course; as well as the platform being enriched with more features the more organizers buy, giving XING Events more money to invest into features).

Another market entrant could well dethrone XING Events by, e.g., offering an entry management service that is easier to user, cheaper, etc.

So, we put our heads together and thought about what makes XING Events unique, plus how can we build a moat around our business. So that we would not be dethroned easily. What we came up with were direct network effects as PDM to bake into our services, entering the game of platform economics:

XING Events has collected information about millions of events from thousands of organizers: the type of these events, its timing, its length, the prices for all its ticket categories, data about the promotion of these events, detailed information about its attendants, and so on. Also, by means of the number of tickets sold, plus the aspiration level of sales, we could tell whether the event was successful or not.

All this information could be leveraged by means of machine learning approaches to deduce communalities between various events and various organizers. What makes an event successful? When to best start into event promotion in which stage? The more information we collected, the better the recommendations and predictions became.

So that we could ultimately put forward the claim “XING Events. We are thousands of organizers.”

Thinks back of the virtuous circle of “more users” leading to “more utility”, leading to “more users” etc. We see exactly the same circle here. Platform economics at work. The moat has been built, for a new entrant could maybe boast better prices and better functionality for entry management … but not the knowledge distilled from thousands of organizers and millions of events.

Sowing network effects and reaping strong entry barriers

To conclude, direct network effects are one of the strongest PDMs to bake into your product. They are not always apparent – in some cases they are elusive to our eyes, so we have to watch closely to spot them. And they go well beyond the usual suspects of social networks. But when we do, when we spot and harness them to our ends, they are able to build up entry barriers to our product and business straight from heaven.

Now there is only one question open: why are they called direct network effects? This little riddle will be resolved when we talk about two-sided markets and the PDMs that work at their core.

Stay tuned.

Want to be updated on new posts? Just sign up here with your email address: