Product Design Mechanics #7: Infrequent needs are a challenge when designing products and business models. But there is a way out. Let’s go piggy-back!

There are products — including very useful products that all of us depend on — that still have a built-in disadvantage thanks to their very nature. A disadvantage that is hard to deny.

Because they are based on needs that are “low-frequency” per se.

What does that mean? It means the product addresses a need that is very infrequent. The opposite of such an infrequent need is, for example, eating and drinking. These are needs that are clearly high-frequency. Otherwise, maintaining a healthy life becomes quite challenging. Transportation needs are certainly high-frequency, too. News access and information as well.

Buying a car is an infrequent need for most people. You only do it once in a couple of years; unless you are a car addict, collector, or petrol head … but even then the use case is largely infrequent. Even petrol heads do not buy cars every month.

The deplorable fate of Casper

Buying a new mattress for your bed is an infrequent need/use case. too. Casper, the US company and D2C brand (Direct to Consumer) that boasts the best mattress in the world, is struggling because of the infrequent nature of its business: Building up a brand that people have top of mind when they need to (that is, when they come to the point where they realize they need a new mattress) is near-impossible.

Why should you as consumer bother to focus your thoughts on something you do not need at the moment. Being a consumer, you grant mental bandwidth only when a product or service is relevant for you. When it is not, then, well, chances are low you will remember the brand. For 99.99% of your life, thinking about mattresses is irrelevant.

Being burdoned with an infrequent use case as basis for your product, next to building up a brand, building up a customer relationship and loyalty is near-impossible, too. Soon as you have bought your mattress you are happy to not have to bother anymore.

If Casper tries to stay in touch, give some valuable advice how to take care of your mattress, serves stories of other happy mattress owners and so forth, you’d be pretty much annoyed. In fact, you’d see it as a nuisance that might even be detrimental to re-purchase probabilites and re-consideration of Casper.

A customer’s need vs. your product

Moreover, there might be a situation where the need itself is high-frequency … while the product’s use is not. This is why, in fact, many e-commerce players and retailers do not have their own mobile app (anymore).It is an ultimate truth that many online retailers had to learn the hard way:

In the early days of mobile device momentum, that is, the early 2010’s, many retailers believed they needed to have a mobile app. Not just Amazon, but also many smaller retailers in the (German) market.

The rationale was simple: If your service addresses a frequent need, then you’ve got a right to occupy space on the users’ mobile phones. Then a mobile app of yours is a legitimate answer to that need. After all, (online) shopping is a frequent need. Thank God. Because mobile apps only make sense when catering to frequent needs.

Why? Because no user would go to the great length of downloading an app and allowing it to consume limited shelf space (essentially the space on your mobile screen where the apps can be started) if it was for single or one-time use only. In that case, every user would prefer to consume the service by access over the default (mobile) web browser.

So, let us assume retailers X and Y are happily crafting their mobile app because shopping is a frequent need. So far, so good. However, what they failed to consider is the fact that while shopping is a frequent need, shopping at exactly this retailer (X or Y) might not.

Amazon certainly has a right to exist as mobile app on your phone. Many consumers do all their shopping via Amazon and thus come back to the app frequently. But this might not be so for retailer X and Y. Maybe you only shop once with X. Because they had the best offer for a certain item you were longing for. Or they were the only ones that had that particular item you were craving for in stock.

So, it is not only sufficient that the need or use case is frequent. It must be that the consideration of your product or service for that very need is, too. As mentioned before, this is a truth that retailers had to learn the hard way. And some are still learning …

But let us get back to needs that are infrequent per se.

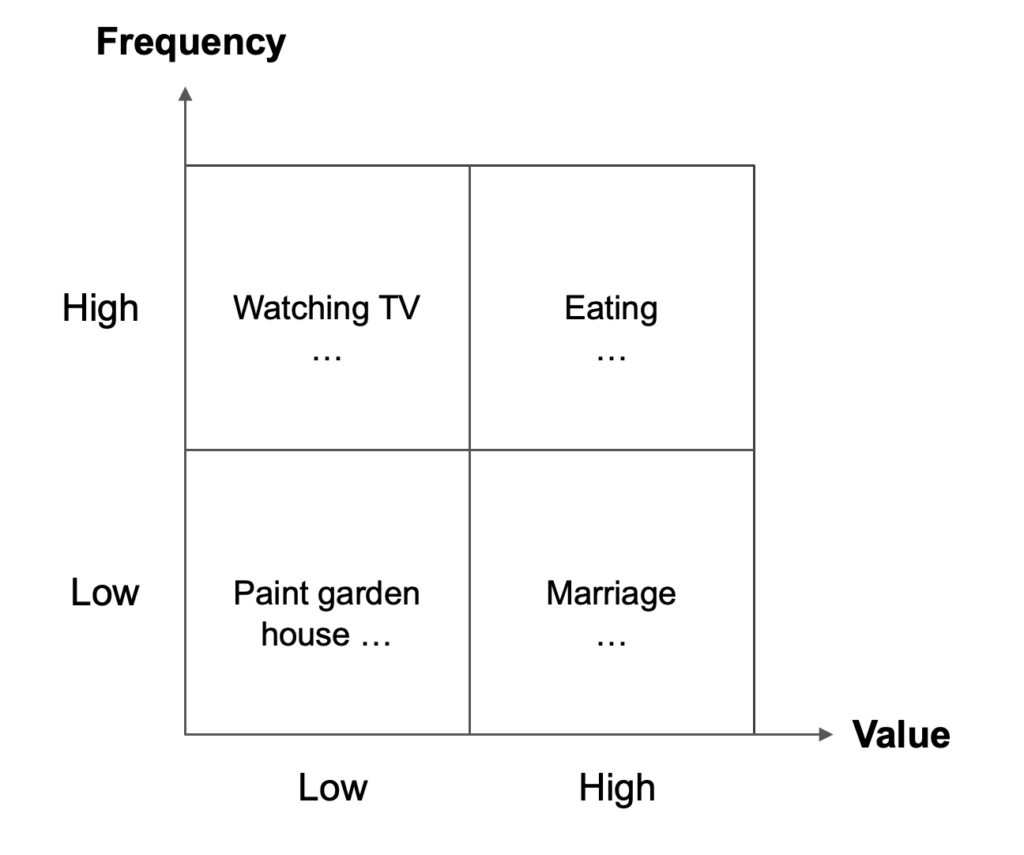

An infrequent need can never be addressed by a frequently used product. Nevertheless, infrequent needs are not necessarily irrelevant or negligible. In fact, there is no correlation between frequency and value. Infrequent, but high-value needs are as common as frequent high-value needs.

Frequency and value are not correlated

See the matrix shown below. Eating is a need that is both frequent (we need to eat at least three times per day) and has a high value (if we don’t eat, we will cease to exist). That’s why food delivery service platforms are highly en vogue.

Painting the garden house is on the other side of the spectrum. It is something we do not do very often, probably no more than once every five years. So it is infrequent. At the same time, it does not change our life (much) for the better or does not help us much to stay alive. It has a low value, too.

A marriage — and this might be my highly subjective view — is an event that occurs infrequent, unless you are a Hollywood superstar. And even in that peculiar case I do not know of a single star that has managed to get married more than once a year.

While it is an infrequent event, it has still a high value to the parties involved. In fact, it is life-changing.

Accepting the fate

So, when our business gravitates around a use case that is per se infrequent, we have to accept this tough fate. We can rarely modify the use case’s temporal nature. E.g., however hard we try, marriage will remain infrequent. We will inevitably fail in our endeavor to change this behavior.

However, we do not necessarily need to leave it with that. Nil desperandum: While we cannot change the core need’s temporal nature, we can complement this need/use case with another one that exhibits high frequency.

That’s what I call the High-Frequency Piggy-Back PDM.

Riding piggy-back to increase frequency

It is a new name for a phenomenon that has been there for a long time. Even before the digital age. But like so many other PDMs, it has not been made explicit, not been mapped out and given a name of its own right. So I dare to give this baby a name.

But where can you see this formerly unnamed baby?

For example, most do-it-yourself (DIY) stores (e.g., OBI, hagebaumarkt in Germany) have a hard time bringing their non-professional audience back to the point of sale, i.e., the local store. Many products you can buy in a DIY store just are not so high-frequency. Oftentimes, you as a consumer have a specific DIY project (like building and painting a garden house) … and then it is over. Or there are tools like a lawnmower — which you need regularly, but which are replaced only every 5-10 years.

So how to bring people back into the local store more frequently? The answer is “screws”.

Screws are unrewarding products in many regards: The store owner needs to deal with myriads of different screws in terms of length, material, purpose, etc. Moreover, screws take up massive shelf space in the store. Sadly, they are low margin. So why would you as DIY store owner want to trade in screws?

Because screws are exactly your piggy-back scheme.

They may be low-value for the consumer (in most cases), but she needs screws quite regularly. So, screws are the reason for consumers to come back to the DIY store. And once they are there, they think of many other things they could use and thus buy. Things that are a lot more high-margin than screws and which justify the store’s economical raison-d’être.

Furniture shops switching frequencies

Other attempts to switch frequency of non-digital retail businesses can be observed in furniture stores: Buying furniture is also a need that is quite low-frequency. Sure, when you move, this need becomes intense and acute. But beyond that point it is not your primary concern.

So how to stay relevant and make people come back more often? Trying to directly work on their furniture buying behavior is certainly futile …

But as opposed to buying furniture, people need to eat and drink every day. So many furniture stores boast full-fledged self-service restaurants that offer lush lunch meals for small money. This way, they manage to attract people for the sake of grabbing a good and cheap meal … and, as some sort of a nice side effect, expose them to their world of furniture.

The good old department stores, nowadays counting among the first casualties of electronic commerce, also had their way of boosting their low-frequency products: have a look at the design of the various levels of a department store.

Oftentimes, the goods that are high-frequency, where there is a high probability that you as consumer come by to buy, are put into the top levels:

These products, that’s what you come for anyway; so you are forced to pass through all the levels of a department store to get there. And escalators are always designed so that you need to walk through the entire floor to get to the one which takes you to the next level. Inevitably, you are walking by all those infrequent products … which helps them to stay relevant in your mind.

The elegance of digital real estate

However, a particular elegant case for the High-Frequency Piggy-Back PDM stems from the universe of digital business models:

Zillow is the number one real-estate portal in the US, the undisputed incumbent. People go there if they search for new homes. Likewise, real estate agents cannot escape Zillow and go there to publish the homes they have on sale.

For you as a consumer, finding your new home is clearly high-value. But it is also low-frequency. Surely, in those 3-9 months where you are looking to find a new place called home, the activity is intense. You use Zillow’s touchpoints, its web portal, the mobile app, on a daily basis. Maybe even many times a day. But beyond this intense period, there is no need to stay in touch with Zillow.

For you as a consumer, the brand and its promise fall into oblivion. So how could Zillow stay relevant and top of mind for you in this temporal valley of despair until you again switch homes?

The answer is a thing called Zillow Zestimates.

Zilllow Zestimates are a clever thing: Enter the address of a certain house and Zestimates will give you an estimate of what it is worth. It is easy, it is low-barrier, it is fun to use.

A nice pastime catering to mundane needs such as your very curiosity: Let’s see what my neighbor’s or my boss’s house is worth. Moreover, it is a use case that is mobile by design: you walk past a building you find interesting … just pull out the smartphone from your pocket and let Zillow give you the Zestimate.

While finding a new home is high-value, the use of Zestimates is clearly low-value. As said before, it is rather a nice pastime. However, while finding your home is low-frequency, Zestimates are utterly high-frequency. You can do it wherever you may roam, several times a day.

Zestimates is integrated into the Zillow mobile app. So in order to use them, you have to …

- download the Zillow app

- use the Zillow app

In that sense, one could say that Zestimates are the Trojan Horse that creates touchpoints with the Zillow brand over and over again.

It makes Zillow — as well as the primary purpose that Zillow stands for, i.e., helping you to find your new home — stay top of mind. Zestimates are the screws in your DIY store. Or the uppermost level in your department store that you access often … while being shown around all the other lovely things in the department store, too.

Zillow’s icing on the cake is that it all feels natural and just right. Because the Trojan Horse, Zestimates, fits so well into the stable of Zillow’s primary concern, namely real estate. Unlike, e.g., lunch meals and furniture.

Common pairings

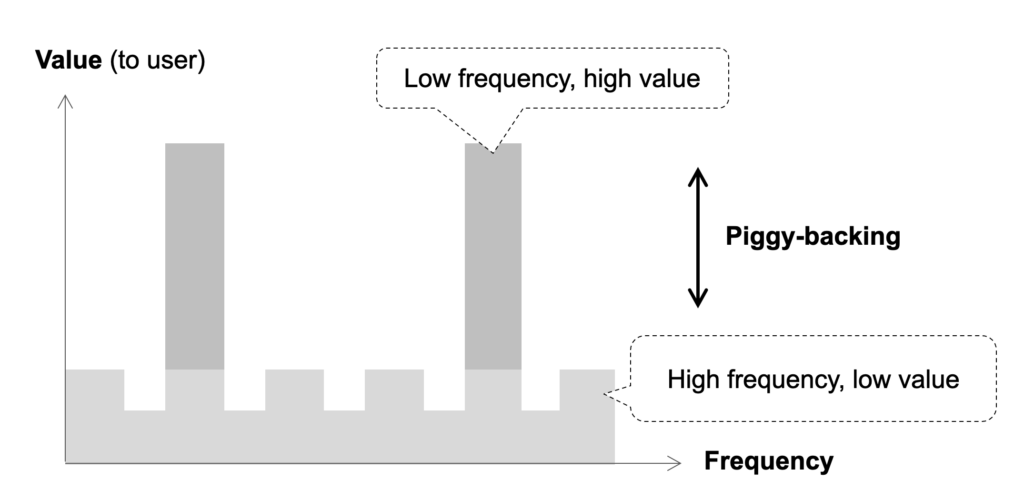

An interesting aspect about the High-Frequency Piggy-Back PDM is that it often comes in a constellation where a low-frequency/high-value need/use case is taken piggy-back by a high-frequency/low-value one.

While this is not an immutable law, it is still a statistical matter that has a clear rationale:

If the core of your business is a use case that is low-frequency, its value must be high … because if it was not, then you are wasting your time fighting a battle you cannot win.

But why are the high-frequency piggy-backers so often low-value? Because if they were high-value, then they should be the core of your business rather than a mere supporting act.

While we have seen examples of the High-Frequency Piggy-Back PDM from pure stationary trade (DIY stores, department stores, furniture shops) as well as pure digital (Zillow), there are also instances of this PDM that can be labeled as hybrid, bearing traits of digital as well as offline retail.

Hybrid pigs

Obi, one of the biggest DIY chains in Germany, is exploring piggy-back frontiers beyond screws. In order to stay relevant as brand and get people back into the brick and mortar stores, they have engineered CRM instruments to provide consumers with relevant content and information:

Taking care of your lawn is not an easy challenge. I can tell from my own, rather fruitless experience. So Obi has crafted a program that lets you define which lawn you intend to grow … and then gives you, on a near-daily basis, ad-hoc information on what to do next. Today, you need to sow the seeds. Tomorrow, you need to water the lawn etc.

This way, Obi manages to steer away from (low) assortment frequency towards (high) everyday frequency.

While notable landmark examples for High-Frequency Piggy-Back, like Zillow, do exist, it still is far from being a mainstream strategy.

Sure, baking this PDM into your product or business model is not a low-hanging fruit that can be reaped at low effort: Finding that high-frequency (and low-value) use case which can be the vector for your core business model is not an easy task … nor is it the challenge of truly developing that use case over time into one that is used on a high-frequency basis by your users.

However, you do not necessarily need to build up the high-frequency feature from scratch. There are many apps out there that are just that, high-frequency and low-value.

Arranged marriages in the app space

For instance, take the plethora of weather apps out there. A weather app is one that you use several times a day — high frequency in its purest essence. They boast usage frequencies that even retail apps of high profile players like Amazon can only dream of. Nevertheless, while the weather app is helpful, it is not life-changing, so rather low-value. You could make the same case for street map apps, like Google Maps or Apple Maps.

While this kind of mobile apps — let us stay with the weather apps — boasts high frequencies, they still oftentimes lack monetization power. In many cases there is just the integration of classic display ads that helps them earn money. Or a low monthly usage fee based on freemium.

However, rather than relying on ads as source of monetization, these high-frequency/low-value apps would be perfect marriage material for solid low-frequency/high-value business models. Strangely, few people appear to think about these symbiotic alliances. At least I have not seen many of them so far.

To summarize, the High-Frequency Piggy-Back PDM is one that has not been invented in the digital age for sure. Just as the DIY store example shows, they have been around much longer. But the digital space offers new opportunities that are much more elegant, esthetic, and effective, just as the Zillow example demonstrates.

And it is not a pattern (or PDM) that has been fully exploited so far. In fact, just the opposite is the case. So, opportunities are rife to be captured, even though the coupling of low-frequency/high-value cases with its piggy-back counterparts are not an easy intellctual pastime.

But, as we know from good old Shakespeare, “the course of true love never did run smooth”.

Want to be updated on new posts? Just sign up here with your email address: