Product Design Mechanics #5: We look at a pattern where business models applying the PDM at hand put companies under pressure to buy their product. Interestingly, these business models are most often sailing under the flag of transparency and democratization.

Not all is what it seems. This holds true ever more so in the digital space. By now, there are numerous streaming video series on Netflix and Amazon Prime that lay out the Silicon Valley’s duplicity in a funny and satirizing kind: on the one hand, there is the messiah-like founder that heralds salvation from her or his product for all mankind (in many cases, this messiah listens to names like Mark Zuckerberg or Larry Page). On the other hand, you are shown the perfidious actions that these messiahs put to use in order to drive their product’s revenues, not always to the better of mankind (euphemistically spoken).

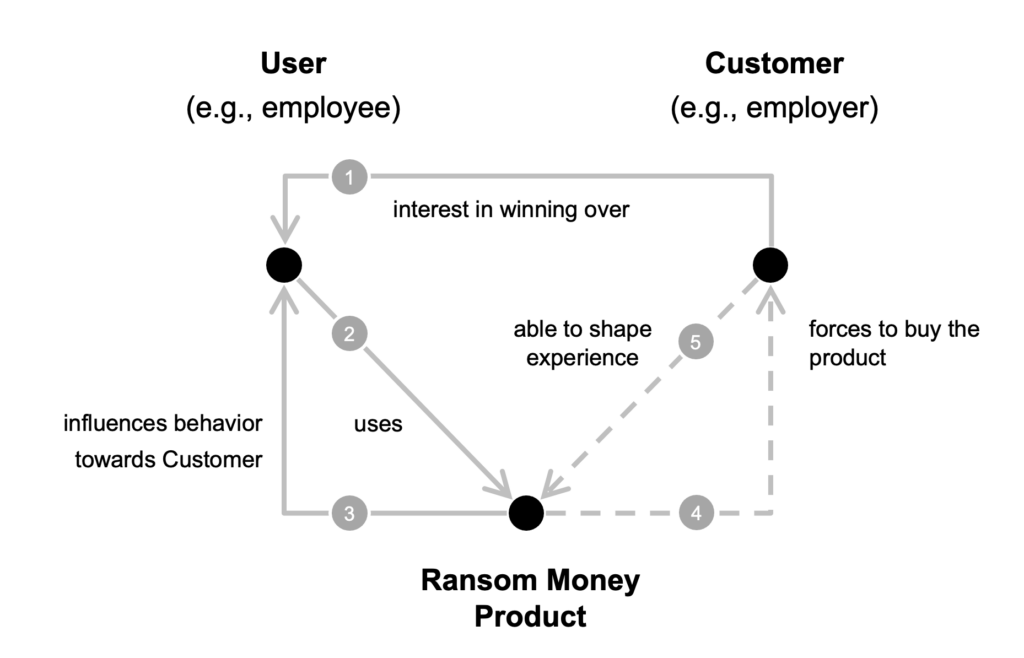

The same holds true for a Product Design Mechanic that is the subject of this article. I labeled it the Ransom Money PDM.

First of all, we all agree that ransom money is a bad thing. One could even call it evil (which takes us back to the before-cited Silicon Valley messiahs, where one of the principal players once stated that “don’t be evil” is their mantra).

What is ransom money, after all?

But why is ransom money so evil? Let’s have a closer look at the abstract model behind ransom:

A certain party C knows that a party B is important to party A. Because party B is in a romantic relationship with party A, is the daughter or son of A, a close friend, and so forth. C is interested in money, but A wouldn’t pay any money to C because there is nothing that C has to offer. C changes this situation by taking B as hostage. Now C does have something that matters to A (namely B) and for which A is willing to pay money, say amount X. A will pay X in order to restore the original situation (which is that B is free). The delta versus the starting state is that C now has increased her wealth by sum X, while A’s account balance has decreased by the same amount.

Two things have happened that are questionable from an ethical perspective:

- C has taken B as hostage, certainly against her will. This is not only ethically questionable … it is an outright crime

- C has intervened into the relationship of A and B (they don’t have access to each other anymore) and uses the power she or he exerts on B to drive A’s behavior (making A pay money)

The Ransom Money PDM, which can be observed in a number of today’s products, certainly does not make use of the first-mentioned aspect. Then it would not be a PDM, but a criminal act. But the second one, the exerting of power on B to drive behavior on A’s side, describes quite accurately what the PDM is all about.

The shiny world of Glassdoor, kununu, and friends

Let us turn away from the dark world of ransom money, crime, influence, and bad behavior. Just for a while. And let us have a look at the radiant and shiny world of better working lives, power to the people, new work, and – above all – uncompromising and relentless transparency.

At the center of workplace and salary transparency are companies like Glassdoor (the US incumbent, acquired by Japanese HR giant Recruit in 2018 for 1.2Bn USD) or its rival counterpart kununu, which prevails over Glassdoor in German-speaking countries.

What both platforms do is to give workplace insights for companies, which is normally hard to get (unless you know some people from the company you are interested in). This workplace transparency is established by collecting reviews of employees and former employees of each company, inviting them to rate their experience with the employer along a set of criteria like leadership, culture, communication, team spirit, perks, and – of course – salary. Moreover, the person writing the review is also encouraged to leave textual comments next to the quantitative survey.

This is a great help to employees as it sheds light into an area of opacity, enabling them to get insights where there had only been the one-sided self-presentation of the company itself. Surely, the new transparency brings up other concerns, like, e.g., fake reviews, as well as the problem of asymmetrical incentive to actually write reviews: critical voices state that it is oftentimes rather the unsatisfied employees (or ex-employees) that have discovered Glassdoor as a tool to air their dissatisfaction. Wounded feelings are a strong driver and trigger of behavior.

On the other hand, if you are a happy and satisfied employee, there is normally not an equally strong trigger that makes you navigate to Glassdoor and leave a rating there. So Glassdoor and kununu oftentimes become ranting platforms.

Anyone can start the fire

It is normally not the company itself that sets up a Glassdoor/kununu employer branding page (as these pages are most commonly called). Anyone can. So, suppose that ExampleCo is the company we are talking about. ExampleCo is being rated by (ex-)employees and applicants alike for how good they deal with employees. ExampleCo might not even know. But they will find out soon, especially when the ratings are bad and ExampleCo is faced with reduced job applications or applicants telling them that Glassdoor/kununu made them skeptical regarding the right fit.

What can ExampleCo do in order to improve its rating and representation on Glassdoor/kununu? Very little.

Unless they pay.

If they decide to purchase the paid package (which is never cheap), they do not only buy the possibility to work on the visual appearance of their ExampleCo employer branding page on Glassdoor & friends. They do not just buy the means to adapt it to their unique CI and write some sweet and cozy heartfelt text. They also get the opportunity to act on the presentation regarding the reviews.

For instance, with Glassdoor, they get the possibility to fix one review, so it is always visible on top of all others. Well, which one might ExampleCo choose? Certainly not the most critical, but rather a complacent one. Moreover, if ExampleCo pays, there will be support by experienced Glassdoor staff. And this includes flagging particularly negative reviews (which is not possible for the non-paying “customer”).

Of course, paying for the premium product does not mean that ExampleCo can completely turn around its representation and public sentiment 180° (in case it is negative). This would certainly fully undermine Glassdoor/kununu’s credibility in the eyes of the employees/users. But it certainly helps to turn ExampleCo’s reputation by 10-20°; which is already helpful, since good and skilled employees are a scarce treasure and the war for talent is raging as it has never been before.

It is a fine line of being credible to the user while charging companies like ExampleCo for boosting their representation.

At any rate, it is a perfect example of the Ransom Money PDM: ExampleCo has an interest in winning over people, turning them into employees. These people naturally happen to use the Internet, and they become users of Glassdoor/kununu. As Glassdoor collects and displays company reviews (amongst them reviews for ExampleCo), it influences their behavior: “Bad ratings on Glassdoor? Uh, better not apply at ExampleCo!” And ExampleCo can do nothing against this influencing.

Except for buying Glassdoor’s product, the employer branding page. ExampleCo is literally forced to do so. Only then it becomes enabled to positively spin the employer branding experience for the precious users of Glassdoor’s services (who happen to be prospective employees).

Ransom Money goes beyond employer transparency

The Ransom Money PDM can not only be observed on employer branding portals. It is also common to other portals that have made transparency their principal purpose and raison d’être.

For instance, have a look at Trustpilot, a Danish consumer review website founded in 2007 that now hosts reviews of businesses worldwide. Consumer reviews in excess of 1 million reviews are collected every month, not a small amount indeed. The site is based on a freemium business model: it is of course the companies, not the consumers, that pay; but they can use a certain extent of Trustpilot’s services for free.

Like other review platforms, e.g., ekomi or Trusted Shops, Trustpilot had (and has) to face criticism emanating from fake reviews. Which is of course a major issue these portals have to tackle, and a major threat to their very existence.

However, there is another criticism that is also put forward when talking about Trustpilot. And it falls, as you might have expected, into the domain of the Ransom Money PDM:

If a company or brand, let’s take again ExampleCo, buys a package from Trustpilot, they get a lot more tools to boost their representation. Want to get an idea what that could be? Here are two examples. However, dear faithful reader, please be aware that these might not be in place by the time your eyes hit these lines. It does not matter, though, because this article is about abstract models and not so much about shedding light on specific companies and their inner workings. That said, I am convinced there are still other (new) features in place that make the attribution of Trustpilot to the Ransom Money PDM still valid.

The first example is the Trustpilot’s Facebook plugin, which is accessible to Pro subscribers for around 600 USD per month. By means of this plugin it is possible to only display reviews that exhibit a certain score: “Choose the number of reviews that you want to display from the drop-down menu, then select the rating that the displayed reviews will have”.

Well, when ExampleCo has been put under pressure thanks to Trustpilot making consumer sentiment around ExampleCo transparent, then here is the tool to polish that very transparency and make it shine.

Second, paying companies can make use of the Trustbox feature, which allows a website to boast embedded Trustpilot reviews. Similar to the fancy Facebook plugin, this box can be configured to only display reviews with a minimum rating or above: “Displays the star ratings that you select, for example, all 3-, 4-, and 5-star reviews.”

Trustpilot states that by using the Trustbox on the website, consumers are not shown the full and accurate picture of all consumers’ opinions. Nevertheless, this bias is not revealed in the widget itself: The Trustbox does not contain any hint that the review selection is filtered, thus giving a misleading impression to consumers.

Physicians are not safe either

As said before, Ransom Money is typical for all sorts of portals hailing transparency. Especially when this form of transparency is connected with a negative skew, as it is the case for workplace transparency where the unhappy are more prone to provide ratings than the happy employees. Why? Because the negative skew increases the need to act on it, increasing the likelihood that the victim will pay the ransom in order to restore the old order.

Yet another transparency-hailing type of portal is that of physician rating platforms. In Germany, jameda and doctolib are the incumbents. They create transparency by allowing patients to rate their doctors. So these doctors might one day wonder when they google their names and happen to find their profile on one of these two portals … though they never created that profile.

Here, too, we have the situation that the urge to rate their doctor is certainly higher on the side of those patients that are unhappy. How to act, being a doctor? How about paying money to obtain some control over your profile.

The long gone days of “don’t be evil“

Besides all these transparency platforms, there is another digital superstar that we may count among the absolute masters of Ransom Money (thanks to Artem Linden for pointing me to this one). I am talking of no one less than mighty Google. The company that once put “don’t be evil” as their mantra.

They created a particularly perfidious kind of Ransom Money. And they had to fight hard in court to keep it. But they won, alas.

Of course, it extends to the realm of SEA, Google’s primary source of monetary bliss. When you enter the name of a company, product, or brand into the famous Google search box, then on top of the page you are shown a number of around two to four paid ads. This practice is called “brand bidding”. Say a user is searching for “Uber”. It is very clear where he wants to get, there is no denying. Still, Lyft might want to sneak in and reroute the user’s journey to its own site. It only has to provide a search ad and a bid for the search term “uber”. If uber does not provide a search ad and a bid that is higher than that of Lyft, then the user will get to see the link to Lyft before that of uber on the SERP. One could say that Google takes the user as hostage. A user whose attention uber has righteously earned before.

Is it legal? Yes it is. The only constraint is that Lyft (to stay with the example) may not mention the term “uber” in its ad copy.

The whole story becomes even more perfidious when you think of all the users who type their query into the browser’s URL bar, which then submits the entered terms to the default search engine in case the typed text is not a valid URL. So suppose you use Google’s Chrome browser, type in “uber” into the URL bar (because you are too lazy to type “uber.com”) and are then redirected to Google’s SERP for “uber” … which shows you an ad for Lyft as topmost entry. Unless uber pays to appear before Lyft.

A perfect case of Ransom Money, but certainly not of “don’t be evil”.

Those who pay are more equal than others

The Ransom Money PDM is certainly one to count amongst the darker PDMs. Companies are put under pressure to act and pay money. Interestingly, the pattern mostly applies to businesses that pretend to be just the opposite: All about transparency, all about democratization of opinion, all about relentless truth. Be it in the space of employer branding and workplace transparency, or be it in the space of consumer ratings.

While there certainly is truth to it (that is, to the fact that transparency is per se a good thing and that these models help to improve transparency), there is likewise truth to the dark side. Namely that money can give a positive spin to that “transparency”. Some are more equal than others. Namely those that pay.

Want to be updated on new posts? Just sign up here with your email address: