Adjacency businesses in classified portals (that is, services related to the transaction that go beyond the core portal search), have become en vogue as strategic levers. However, they cannot be your prime strategy.

Nota bene: This is a lengthier article than the ones I usually put on my blog. This is because there is some need for background to appreciate the stuff I present here, like what classified portals actually are and network effects. If you are familiar with those, feel free to skip the first paragraphs.

Classified portals, such as real estate or (used) car platforms, are massively profitable. Their core business is to connect sellers with potential buyers. While generally for free for the buyer, they charge the seller a listing fee plus various gimmicks that allow him to boost the visibility of his offered object.

Adjacencies are services that go beyond the portal search, that is, the connecting of a buyer with a seller (of a house, car, or whatsoever). In case of cars, this might be a service that has the desired car checked for damages the layman’s eye would not be able to spot. Or a consumer loan to finance the car. In case of real estate this could be the mortgage or moving service. But the core service of classified portals is search, connecting buyers with sellers (and thus objects, i.e., cars, houses, etc.).

So they fall under the concept of marketplaces. Two-sided in case of e.g., car platforms (car seller and car buyer), even three-sided in case of real estate (we’ve got the agent, owner, and buyer/tenant). This is also the reason why they are so massively profitable: Marketplaces are hard to build up, but even harder to attack once they are established as incumbents. This oftentimes results in “winners take all” markets. This monopoly (or duopoly at best) comes with a premium for the marketplace’s seller-side (which is where the majority stake of money comes from.

The power of networks

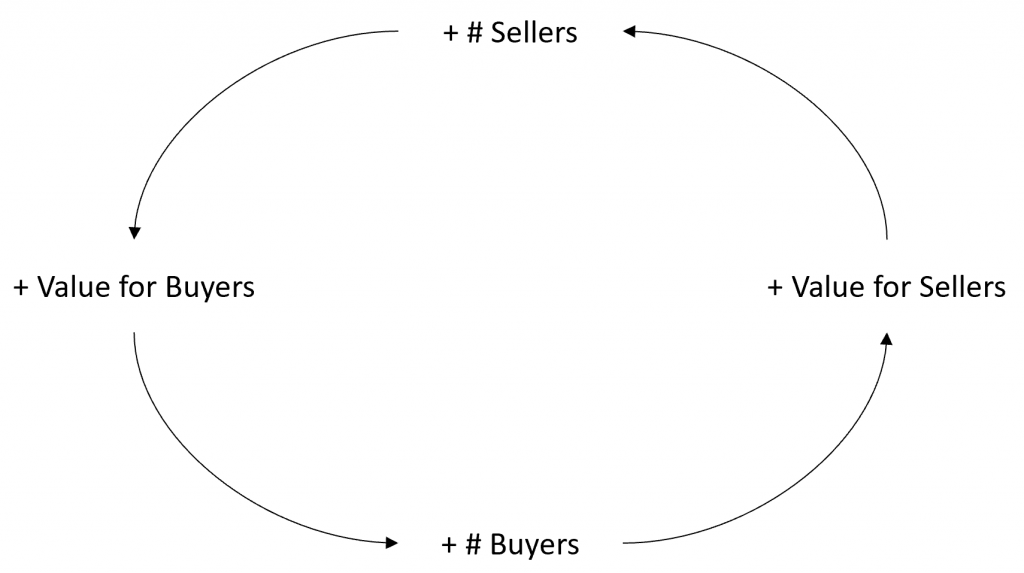

Why is this so that they are hard to build up, but also to attack? The reason is connections. That is, the marketplace’s connections with a plethora of buyers and sellers it is able to attract. The power of these connections come from the often-cited “network effects”, also called “Metcalfe’s Law”:

In networks, such as as social networks like Facebook, Linkedin or XING, the value for the user is determined primarily by how many other users are there: If there are few of the people you want to see, even the nicest product features will not be able to convince you to go there. On the other hand, if all your peers are there, then there is implicit pressure on you to be there as well. Be there or be square.

Metcalfe’s Law says that the value of the network to the user is determined not just linearly in terms of the other users, but in a super-linear fashion. That means that if the number of users doubles, the value increases even more than double as much to you as users. Contrarily if you have a network whose number of users is half as big as that of another, its value to the user is less than half.

Network effects do not only appear in the obvious shape of (social) networks. Network effects also occur in more arcane settings. For instance, in the 90s, one principal reason for the massive success of the PC over Apple’s Mac were network effects. Even though Apple had the better product. Back then, interoperability between systems and OS was very limited.

That is, a document written in the word processor on a PC could not be read and edited on a Mac and vice-versa. So the decision whether to buy a Mac or a PC was largely dominated by which OS your relevant immediate peer group was sticking to: If your friends or colleagues where PC guys, so would you. Otherwise you wouldn’t be able to exchange documents, files, and software. A perfect example of network effects.

Marketplaces are even stronger than networks

What is true of networks is even more so with marketplaces. While networks are hard to build up and to attack, marketplaces are even harder. Why? Because they are (at least) two-sided: In a network, you need to build up just one side, the side of users (e.g., the users on Facebook), which is difficult because of the said network effects at work. In marketplaces, you need to build up the side of the users (commonly the buyers; let’s call it the C-side) and the side of the sellers (the B-side). At the same time.

The complexity arises because one side has a direct effect on the other: If you don’t manage to have many sellers (and thus objects to sell on your platform), it’s safe to assume that the buyers won’t come. And vice-versa. This is called indirect network effects, which are defined as follows: “With indirect network effects, the value of the service increases for one user group (e.g., buyers or sellers) when a new user of a different user group joins the network.”

The marketplace’s center of gravity

Every business model has a center of gravity. That is, its very core that needs to be embraced by the strategy of players willing to make a stand in the market.

The center of gravity for marketplaces, while being two-sided, is clearly the C-side, the quantity and quality of consumers that you are able to summon on your platform. If you have the buyers on your platform, the sellers will come automatically. And they will be willing to pay you for giving access to the consumers.

That’s why marketplaces oftentimes follow a “winners take all” pattern. That’s why the successful ones are amongst the most profitable business models you can think of. For instance, Rightmove, the incumbent in UK in real estate classifieds, has an unbelievable EBITDA margin of 76%, and a productivity, measured by revenue per employee, of > 500k GBP. Show these numbers to someone working in retail and you will see her cry.

In fact, speaking about real estate platforms, EBITDA margins > 50% are the norm rather than the exception for the national leaders. So Rightmove is not an odd one out.

Digging elsewhere

However, growth might be coming to a halt. The market for used cars in developed countries is not expected to grow massively. Same as for the housing market, where both the number of agents as well as the number of objects are stagnating or declining.

If there is no more volume, then revenue increase must come from getting more money out of the pockets of those offering. Meaning more services or price increases, thus increasing the ARPA (average revenue per agent) in case of real estate portals.

The price increase game has been successfully played for some years, keeps being played but of course is subject to an increasing risk that sellers may revolt, e.g., by looking for substitutes.

Therefore, classified portals have looked to other ways how to generate more money next to the core classified business. An obvious one is of course to put display ads out. However, as Fred Wilson of Union Square Investment bluntly put it: “Facebook and Google have won the ad game, everyone else has lost.” So, this is model is clearly finite.

Enter adjacencies

Another approach is to monetize the buyer (on top of the indirect monetization via classifieds) by means of offering services related to the transaction (i.e., the purchase/rental of the car, house, or apartment), that the buyer needs to consume anyway. Thus making the portal a wonderful one-stop-shop.

Sounds cool, and there has lately been a lot of buzz around adjacencies especially in the real estate portal business:. The Australian no. 1 portal, REA Group, made a significant acquisition by buying Smartline in 2017, aiming to go deep on mortgages. Even more recently, Zillow, the US no. 1, bought Mortgage Lenders in 08/2018. And Scout Group, the German incumbent, has bought Finanzcheck in 2018 for 285 Mio. EUR, aiming in a similar direction.

This is clearly topped by Zoopla, UK’s no. 2 in real estate. Zoopla bases its entire strategy on being a one-stop-shop. This has led the company to invest around 500M GBP since 2015 into adjacencies (see Mike del Prete’s excellent 2018 Global Real Estate Portal Report, which you can download here).

However, while I believe that ramping up your adjacency business as an add-on is totally sound, it cannot be your strategy in a portal business.

The first reason that this is not advised is rather a mild one: Revenues from adjacencies are far less profitable than the revenues from the core classifieds business, as Mike del Prete has shown in the before-mentioned excellent report. They gravitate somewhere around 30% to 40% EBITDA margin … which is still not bad and would still make a retailer cry for joy.

Stepping down the customer journey funnel

The second reason is the true one why adjacencies cannot be your strategy.

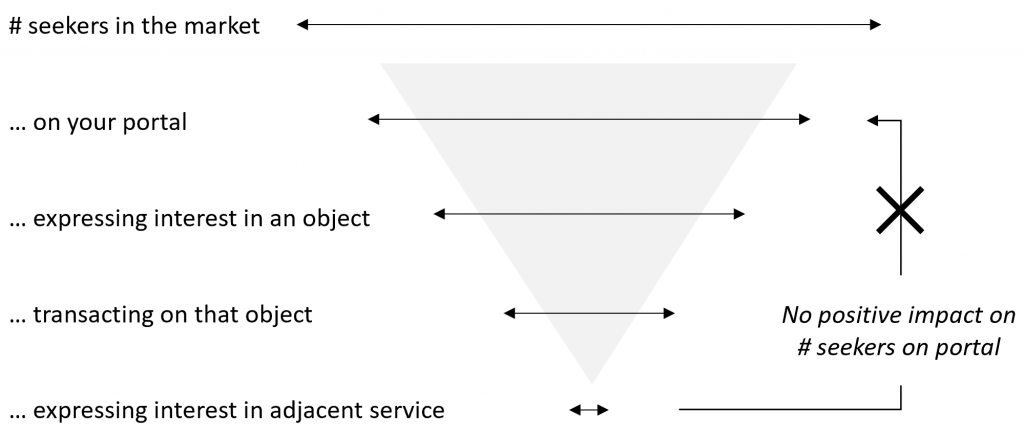

Let us have a look at the funnel logic of the buyer’s journey: There is the overall market of consumers willing to buy/rent in this very moment. Some of them land on your platform. Some of those users of your platform connect to sellers, thus becoming leads to them. And some of them finally do the transaction. Part of those consumers that do the transaction can be pushed into adjacencies, say mortgages or moving services.

So, it is obvious that your adjacency revenues are a direct function of your core business: The more consumers you get to your platform, the more adjacency revenue you can make (assuming ceteris paribus for conversion rates of transactors to adjacency leads).

However, let us have a look if we have a dependency also in the other direction. That is, do adjacencies on your platform (if you have them, which services you offer, the number and quality of partners you have, how well services are integrated …) have an impact on the number of consumers? Do they come to your platform because you offer these adjacent services? E.g., do you visit a portal because you know that you also get a mortgage there in quite a convenient fashion? Put yourself into this situation: I am sure the answer is a clear “no”.

Dig inside yourself

When you are searching for a house, all your focus is on that very activity: the search, the search, and again, the search.

Which portal will you choose? Your number one reason is certainly the penetration of overall objects in the place you are looking for. Followed by which information you are provided along each object that helps you make a decision in your search. This could be a price calibration, information about the seller, and so on. At this moment in time, you do not even think about services you will need after the transaction, such as the mortgage etc. Even if you do it won’t be vital enough to change your mind about which portal to use.

In other words, the offering of adjacencies has zero effect on the number of consumers on your platform. Consequently, it does not nothing to get your network effects going. Finally, it does nothing to address the center of gravity of classified portals, which is C-side quantity and quality. And therefore it cannot be your strategic focus.

Reality check

Let us subject the above said to a reality check as there is fortunately a portal that has gone all-in on the adjacency strategy, Zoopla. Today, Zoopla’s revenues from core portal classified business only represent 25% of its overall turnover. Versus 75% from others, mainly adjacencies. The reason is that Zoopla attempted to differentiate from incumbent Rightmove.

Looking at bare numbers one could say that Zoopla’s strategy paid of: Revenue growth from 2013 to 2017 exceeded that of Rightmove. Today, revenues are almost at par, close to 250M GBP each. Note that Zoopla had around 60M GBP in 2013 while Rightmove could boast around 140M GBP.

As mentioned before, Zoopla paid an impressive total amount of roughly 500M GBP to acquire most of its adjacency businesses. The question is how would these businesses (such as the comparison platform uswitch) have done standalone, without being a part of the Zoopla real estate portal. Again, Mike del Prete has analysed this in his formidable report and concludes that there is little indication that synergies have emerged.

In other words, the acquired adjacent businesses would have developed in pretty much the same way revenue-wise had they not been acquired by Zoopla. Frankly, this is puzzling even when assuming that your adjacency business does not support your portal core much. There should be some synergies, given that you own key access points from where you can funnel users quickly into adjacent services, without them having to leave your platform and search on Google.

If that is really the case, and synergies are zero, then Zoopla could have likewise acquired a supermarket (or any other random business, as long as it showed a standalone growth as nice as that of uswitch & Co.) and earned as many synergies. However, clearly the projection of Mike has to be handled with care as it is just that: a mere projection. We do not know how these adjacent businesses would have fared standalone (as long as we cannot access parallel universes).

Even more interesting is the look to the portal side of Zoopla, which is its origin. Leaving away the acquired adjacent businesses, what is the growth of classified revenues in that same period, from 2013 to 2017. The quick answer is … there is none. Its classified business is effectively flat. If you are in the real estate portal business, this will not help much.

Summing it up

Don’t get me wrong, there is nothing wrong about investing into adjacencies, especially when all the other revenue levers seem to have been maxed oud. In fact, every portal should do it, especially when you are the dominating portal in a market and seek new revenue pools.

However, strategically, it’s an icing on the cake which will not change your competitive position. Therefore …

- As the market’s dominant portal (that has maxed out the base of customers and ARPA), adjacencies are a tool of choice to get growth going again … at least for a while.

- As a runner up portal (like Zoopla), I am convinced this should not be your primary strategic focus. You should rather focus on the center of gravity, the number of consumers on your platform, driven by network effects.

I like to compare adjacencies to a turbocharger: The exhaust gas of all the fuel that has been brought to explosion (and used for propulsion) is compressed and brought to explosion again, for extra propulsion. A turbocharger thus provides an extra to the engine.

However, this extra is fully dependent on the fuel that is burnt in the first place. You cannot build a car just with just a turbocharger. You still need the core engine.

—

Want to be updated on new posts? Just sign up here with your email address:

Hi Cai,

very interesting blog post you wrote there, with a lot of insight.

A few questions arose while reading, like:

What is the overall EBITDA of Zoopla now, with all the adjacencies included? And how much lower is the EBITDA compared to a platform that was in a similar situation like Zoopla (number two in the market?), but decided to focus on the core business instead?

Also, since “Facebook and Google have won the ad game“ should platforms refrain from placing ads? Especially since they might even hurt the core business, by taking away customer attention and thus potentially lowering conversion rates.

Furthermore, shouldn’t a runner-up platform not just focus on the „C-side“ strategically, but also in communicating that strategy to said side? Even more so, when the task at hand is such a hassle, that people would love to have someone „in their corner“ for.

Let me add a small technicality to the turbocharger analogy, so it can be used in a more precise manner in the future: the exhaust gases aren’t actually brought to explosion again. They are used to compress a larger than normal amount of fresh, cold air, which then makes for a more powerful explosion, when combined with unburned fuel. The fact that a turbocharger provides an „extra” to the engine still holds true of course.

Thanks again for the great article.

Best regards

Martin Weiße

Hi Martin,

thanks for your comment, here some brief reply:

– re Zoopla: ZPL has delisted last year, so you won’t find current tradings anymore. For a good analysis of its businesses (and past fins), see the Real Estate Portal Report of Mike del Prete from 2018

– re Facebook/Google: Thinking about whether display ads make sense is a consideration that company leaders of real estate portals continuously think about

– re “C-side first”: Yes, it’s not only a product, but also a brand marketing/PR game

– re turbo: You’re absolutely right 🙂